One of the books that I’m reading for Black History Month 2021

Circumstances of Purchase

Perhaps two maybe three years ago I purchased the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Booker T. Washington‘s Up From Slavery at the Green Valley Book Fair, which is a barn outside of Harrisonburg, Virginia where some clever citizens ply remainders—books printed in batches exceeding demand. OUP World’s Classics have a number of titles offered there. These are books that are published in part because they are sold to college students, but apparently even enough college students aren’t buying. This book cost only $3.50. I also picked up Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and Dante’s Vita Nuova. This was the first of those I’d read, although I’d at least earnestly began the Vita a couple of times before (okay, perhaps earnestly is the wrong word).

Conditions of my Knowledge

Even before I left the small Dorf of Powhatan Point, Ohio—sitting lazily on the Ohio River as it is slowly drained of any economic force by the inevitable closing of coal mines—at the age of 12, I’d already heard the name of Booker T. Washington. I knew that he was Black and that he was an important person but that is probably all I knew.

I knew that racism was “wrong” and “unjust” (woefully weak and inaccurate judgments), but that was merely the empty knowledge of a child parroting what his parents say. I drew no connection between this empty knowledge and participating in elementary school jokes imagining particularly unlucky girls having to kiss Frankie Hawker, the only black boy in our school.

Frankie was older than me by two years, but I would outlive him. As I understood it and still understand it, he died after falling off of the auditorium stage onto the hard concrete floor below, during gym class. He hit his head.

Although I know that there were locker rooms beneath it (the auditorium’s stage was also a basketball court cum gymnasium), that floor always seemed, and perhaps especially so after Frankie’s death, as the hardest ground on the entire earth, so solid that it had to extend far into the core of the planet. That floor refused to offer even the smallest gift of mercy. No wonder it extended down to hell.

The school held a memorial service for Frankie that filled the auditorium with all of the students. This memory stands out because during the service Brandy, a classmate, happened to look at me at the moment I was recalling a funny time I’d spent with Frankie (not at his expense) and smiling. But Brandy was crying, as we were all supposed to be, or at least sad in appearance. I worried my expression would make light of the moment. Did Brandy think that I was a racist?

How did Frankie actually die? Was he not given the same attention at the hospital because of the color of his skin? Was the school partially at fault and consciousness thereof provoked the public memorial service? I do not know. I didn’t go to Frankie’s funeral. That idea never occurred to me.

It could have just been a bad fall. No rail or guard went across the front of the stage. Maybe Frankie never woke up and simply died from a cerebral hematoma . . .

When Booker T. Washington was the age Frankie Died

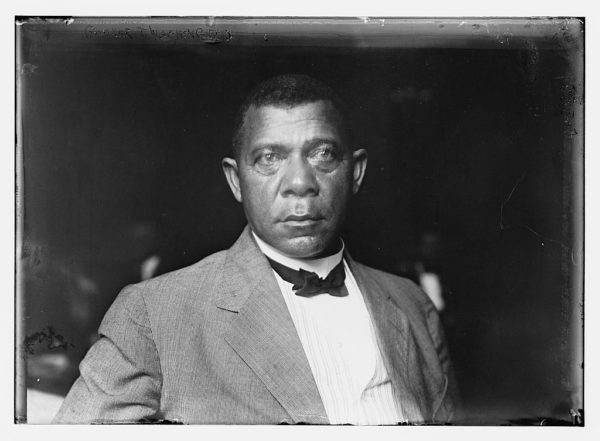

When Booker T. Washington was the age at which Frankie Hawker died, he had only been freed from slavery for five or six years, living in a small encampment/village outside of Charleston, West Virginia called Malden. He wrote his books some thirty years later, after he’d graduated from the Hampton Institute, came back to teach there, and then was tapped by the institution’s head, Brigadier General Samuel C. Armstrong, to start a school in Tuskegee, Alabama.

When he wrote Up From Slavery, he had already transformed that school from thirty odd students in an abandoned, dilapidated house into an institution educating more than a thousand students each semester in a developed campus on hundreds of acres of land. He’d already become known and honored across the U.S., including by then President McKinley and others. He’d married three times and sired several children.

His methods were so well-known that W.E.B. Du Bois had given them critical attention in The Souls of Black Folk. Reading Du Bois’ essay on Washington’s ideas drew his name out of the swamp of my mind, where he was confused with George Washington Carver and Booker T. and the M.G.s (hmm . . . ).

Du Bois taught me more about Washington’s ideas than I had ever known. Perhaps in some history or social studies class, I had been told that Washington had advocated for the education of black Americans (which is at least a partial truth), and the uninteresting, uncontroversial—or more plainly, uncontextualized—appearance of this fact immediately relegated it to a collection of ideas that also ultimately meant nothing.