Part of the series of articles pertinent to Black History “month,”

which for me started in February and is still going strong mid-March.

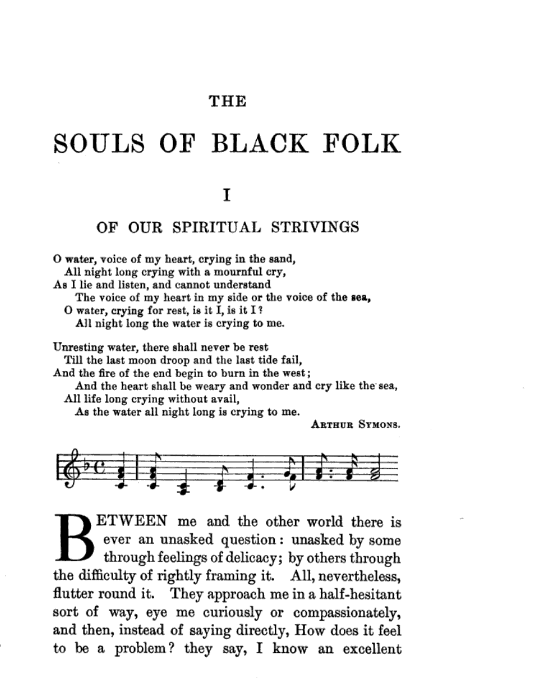

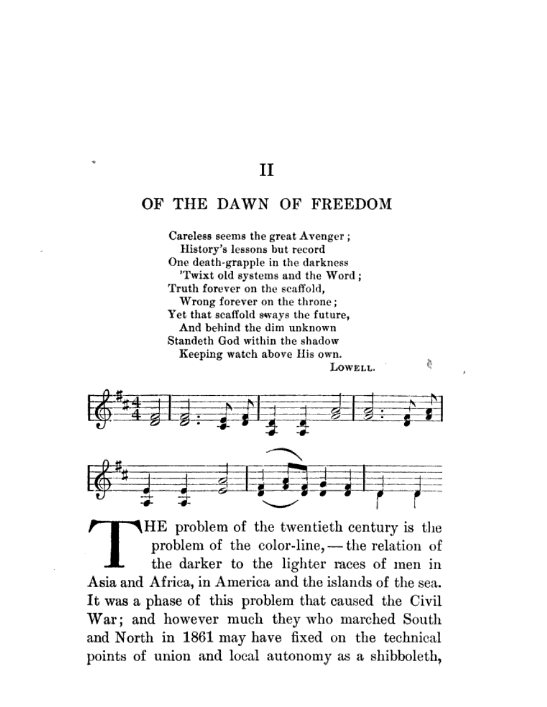

Each chapter of W.E.B. Du Bois’ Souls of Black Folk begins with a short verse and a bar of music. The verse comes from a poet, usually those known during the fin de siècle period (1890-1910) as well as some whose popularity has survived to present day.

When she turns the page to a new chapter of Souls of Black Folk, the reader encounters an excerpt of poetic verse and several bars of music before the chapter’s text proper begins. If she is so gifted, she can not only read the verse aloud, so as to witness its particular inflections, but also hear the music.

What Du Bois intended with the music

Certainly Du Bois intended this when he had the pages so printed, namely, for this reader to not only read the verse (that doesn’t require speaking aloud) but also hear the music as it played. Some gifted readers can read the music and hear the music at the same time. Others, like your author, are limited to seeing the notes and recognizing the crudest patterns.

The beginning of each chapter is a sensual experience, not merely an intellectual act of communication and interpretation between an author and his reader separated by lived distances, historical periods, and incontrovertible cultures. In part, music conveys different notes, various pitches, distinct time and chord signatures.

But music also conveys effects (or affects, if you are of a Spinozan bent).

Musical “information” stands separated as radical a distance from music heard as does the word orange from a single succulent orange peeled and eaten.

Music heard affects: music irritates, angers, soothes, inspires, pleases, provokes, saddens, excites, and even bores—to name just a few affects.

Music in early twentieth-century film

If you watch the 1933 pre-code film She Done Him Wrong, starring Mae West and Cary Grant (and others whose names posterity has mostly forgotten), you will encounter two scenes mostly unrelated to the narrative. In these, Mae West walks onto a stage in barroom (a concert saloon) and performs bawdy songs well-suited to a crowd of drinking men but that would scandalize Christian ears.

Those two scenes are perhaps boring if not perplexing to the contemporary viewer.

For the contemporary viewer, music is heard primarily by oneself through headphones or, heard with others occasionally secondarily, and heard as it is performed very rarely (and suffers in this last instance from a lack of authenticity—it’s different from the original recording).

The idea that we might watch a person sing before us is rather strange, especially if that person is Mae West. But in She Done Him Wrong and other early films, music heard is primarily a social experience. Motion pictures were in the process of supplanting earlier forms of entertainment, such as the radio program during which it was not uncommon for listeners to be enjoined to sing along with familiar songs and before that by roving camps of singers, musicians, and actors who travelled from town to town.

In She Done Him Wrong, Mae West’s performances are a vestige of a past that is now all but lost.

Singing with others, singing a hymn or a melody known well by your neighbors, friends and family is one of the ways through which belonging and identity are felt (and known).

Du Bois’ verse and musical bars

Isn’t it reasonable that Du Bois wanted to share that experience with his reader? Du Bois wanted his reader to hear those bars of music and have something resembling the experience that he had and feel the meaning invoked by that music. All of this before she starts reading, “Between me and the world …”

Isn’t this part of what a title like Souls of Black Folk promises to reveal?