Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is the 1861 memoir of Harriet Jacobs‘ experiences growing up in and then escaping from a North Carolina plantation. The book constitutes a historical document as valuable for its first person testimony as it is for its literary virtuosity.

The facts of Harriet Jacobs’ life

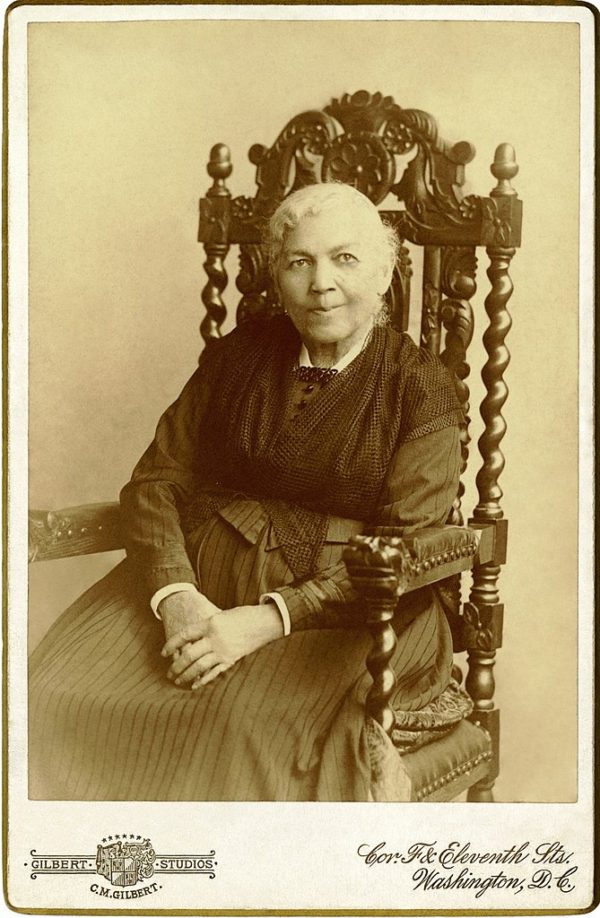

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in either 1813 or 1815 in Edenton, North Carolina, a small city located on the inner banks of the state’s northern shore. Initially she was owned by a genial woman named Horniblow, but after the mistress’s death she was sold to Dr. James Norcom. She lived unhappily in service to the Norcom family until she escaped in 1835. It was not until 1842 she was able to make it to Philadelphia and then to New York city. After the death of her grandmother she finally decided to write her narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, after several promptings. The book was published in 1861. She died in 1897.

In relation to Washington’s Up From Slavery

Where righteous indignation might have been wanting in Washington’s Up From Slavery, Jacobs provides in great and sorrowful detail. But to compare these books is something of a mistake. Incidents is set before the Civil War, whereas nearly all of Up From Slavery takes place after. Up From Slavery is a defense of a social and political movement; Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is a story stoked in the fire of sexual exploitation.

From Jacobs we gain an unvarnished account of the pains suffered by a female slave. What Jacobs suffered she shares with her reader, as well as the reflections on the institution of slavery in a profound Biblical style. She is also simply a very beautiful writer.

“You may believe of what I say; for I write only that whereof I know. I was twenty-one years in that cage of obscene birds” (Jacobs, p. 52).

The cage is not the one holding slaves, I’d wager. This is not to say that the cage is peopled by only individuals of tainted character, although that description describes the primary antagonist, Dr. Flint (the name that Jacobs gives to Dr. James Norcom). Flint is Linda’s owner and tormentor.

“But now I entered on my fifteenth year—a sad epoch in the life of a slave girl. My master began to whisper foul words in my ear” (p. 29).

Slavery is corruption

“Corruption, in this species, is splendid.” When William Gass wrote those words, it was applied to the insects that a unique housewife found dead on her carpet. For Linda Brent (Jacobs’ pseudonym, necessary because she was still a slave when she wrote her narrative) the corruption bears on all touched by slavery. Not only the slaveowners, but the slaveowners’ families as well as the slaves. And the corruption here is moral.

The slaveowner’s tainted by his participation, not because of his belief in the justice of owning slaves, but because of the ethical effects of slaveowning. The slaveowner’s power over others has no limit due to the legal protections afforded, and as a result he gives his desires free rein. For Jacobs, sexual violence is not a mere possibility but a structural necessity: slaveowners who deny their sexual appetites for the female slaves are the exception.

Slaveowners also have financial encouragement to these sexual exploits because the condition of the mother determines that of child. If the mother is a slave, the child will also be a slave.

Empty promises: corruption demonstrated

For years, my master had done his utmost to pollute my mind with foul images, and to destroy the pure principles inculcated by my grandmother, and the good mistress of my childhood. The influences of slavery had had the same effect on me that they had on other young girls; they had made me premature knowing, concerning the evil ways of the world. I know what I did, and I did it with deliberate calculation.

p. 53-4

When the attentions of a white gentleman came to her—an unmarried, “eloquent,” and sympathetic one—she responded naturally despite knowing to where they were to lead.

“There is something akin to freedom in having a lover who has no control over you except that which he gains by kindness and attachment” (p. 54).

Moreover, these attentions also provided an opportunity for her:

“Of a man who was not my master I could ask to have my children well supported; and in this case, I felt confident I should obtain the boon. I also felt quite sure that they would be made free” (p. 55).

Subsequently, two children were born by this gentleman, Samuel Sawyer. After Jacobs escapes, she arranges for Sawyer to purchase her child from Norcom. Then, then Sawyer is elected to Congress, Jacobs obtains a promise from him that her children would be freed (p. 118). Yet the question is repeatedly to make sure that the slaveowner realizes his good intentions.

There are details here that I’ve left out, some of which are especially notable, such as Jacobs’ seven years of hiding in the roof of a shed outside her grandmother’s house.

Interested to learn what else I read during Black History Month, February 2021 edition?