Since the posts on this site (about reading Ulysses or whatnot) are about the experience of reading (and viewing) books (and films), it seems an elision not to say more about the pleasures and pains that attend reading.

Yet the elision wasn’t purely accidental.

Ironically, it’s difficult to put these pleasures and pains into words. But what’s harder still is saying why this experience is important, and worthy of articulation.

Is the Content Why We Read?

When we write and speak about books, most of what we write about is the content of the book, to be crude. In other words, it’s about — in the case of a novel — what the story is and who’s involved and how it unfolds. This content also includes the language of the text such as it is presented below and then dissected through analysis.

Interpretation almost always wholly concerns these things, the content.

Is the Experience Separate from the Content?

The “actual” experience of reading (and why I put actual into quotations is worth consideration) is still separate from this.

Is the “actual” experience the one where it is understood? If so, then that would put the emphasis on content. Content would be the criterion for “actuality.”

Equally — and this is my fear — does the “actual” experience bear on a subjective experience, something unique to the person?

Pleasure and Pain as Reading Criteria

Our culture conceives reading as a recreational activity if not a vocational responsibility. As recreation, reading effects pleasure when successful. So we say, “I really enjoyed it.” Or even, “I couldn’t put it down.” We want the book to completely envelop our consciousness.

By contrast, when the reading is difficult because it provokes confusion or irritation, we judge the book to be “bad.” “I couldn’t get into it” ends up being a charitable articulation as it implies that the reader is responsible. More frequently the book is “boring.”

To stave off these reactions from my philosophy students, I’d tell them that “no pain no gain” should be their goal. In other words, if the reading wasn’t painful, they weren’t doing it right.

Yes, I would actually say that. And I still think that’s right.

The Pain of Reading Ulysses

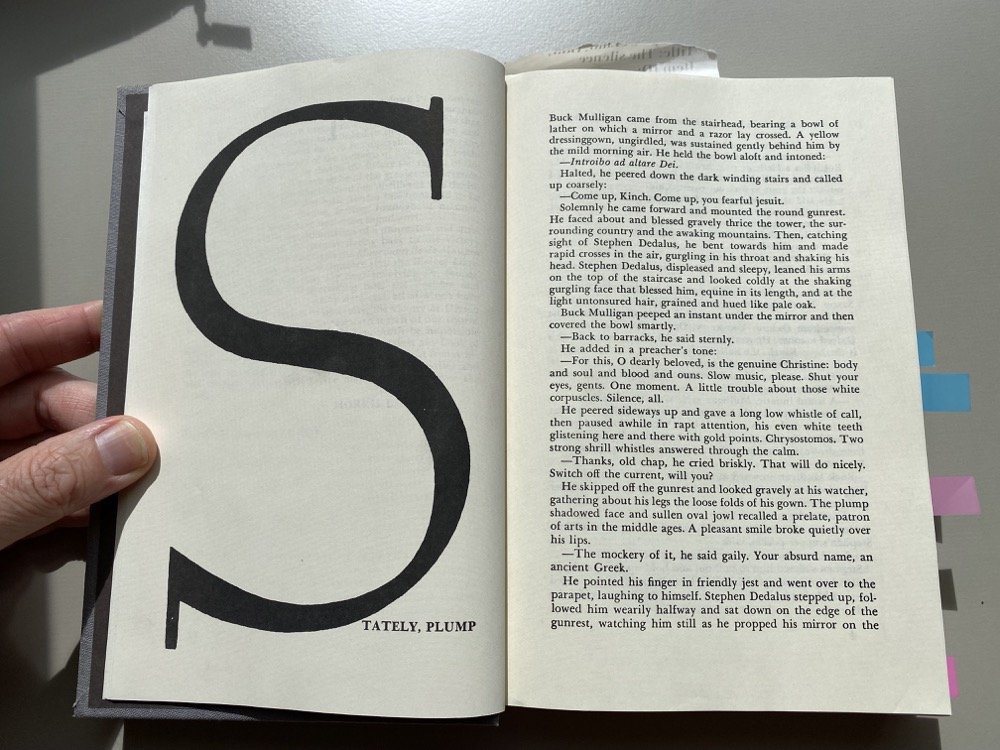

Reading Ulysses by James Joyce has reminded me of that because it’s been difficult, painful.

To contextualize this, it’s not painful in the way that G.W.F. Hegel‘s Phenomenology of Spirit is painful. The Phenomenology is, I think, the hardest book that I’ve ever read. It is an 1807 philosophical work written in a diction by itself difficult to work through, apart from understanding what it the diction is supposed to express.

Whereas reading literary works is quite different because there is no point like there is in a philosophical work. We don’t read a literary work to learn that Joyce thinks spirit continually deceives itself about its self-knowledge (one of the “points” of Hegel’s Phenomenology).

Yet I do not want to say that there is no “point” to a literary work.

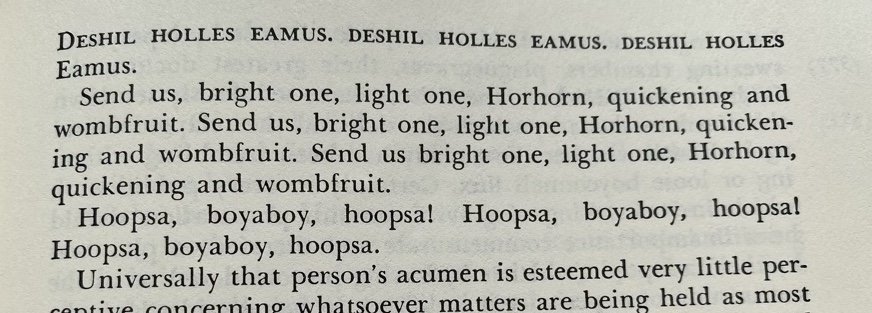

The beginning of “Oxen of the Sun,” from Ulysses. This section is not named “Oxen of the Sun” by Joyce, exactly, but each part does coincide with a section from Homer’s Odyssey.

A passage from the section of Ulysses called “Oxen of the Sun.”

DESHIL HOLLES EAMUS. DESHIL HOLLES EAMUS. DESHIL HOLLES Eamus.

Send us, bright one, light one, Horhorn, quickening and wombfruit. Send us, bright one, light one, Horhorn, quickening and wombfruit. Send us bright one, light one, Horhorn, quickening and wombfruit.

Hoopsa, boyaboy, hoopsa!

Hoopsa, boyaboy, hoopsa!

Hoopsa, boyaboy, hoopsa.

The first sentence of this was wholly gibberish until I read Stuart Gilbert’s James Joyce’s Ulysses, which explained that “Deshil” is Gaelic for down and right and “Holles” is the name of the street where the maternity clinic is that is the scene for the episode. “Eamus” is Latin for “we go.”

The second paragraph is an invocation, with “bright one, light one,” a reference to Helios, the Greek god whose island is where Odysseus and his men stay. “Horhorn,” to the administrator of the maternity hospital during that period, Andrew J. Horne, but also to the phallus (oh don’t get me started). And wombfruit seems self-explanatory.

The third paragraph/section is something said by midwives in birthing.

These parts, even if unclear, I could read through and gain some sense. But then came the following, which really provoked pain in that I could not imagine making sense of this.

Universally that person’s acumen is esteemed very little perceptive concerning whatsoever matters are being held as most profitable by mortals with sapience endowed to be studied who is ignorant of that which the most in doctrine erudite and certainly by reason of that in them high mind’s ornament deserving of veneration constantly maintain when by general consent they affirm that other circumstances being equal by no exterior splendour is the prosperity of a nation more efficaciously asserted than by the measure of how far forward may have progressed the tribute of its solicitude for that proliferent continuance which of evils the original if it be absent when fortunately present constitutes the certain sign certain sign of omnipollent nature’s incorrupted benefaction.

Ulysses, p. 383

Gilbert, others, remark that this is an English transcription of Latin text. Which sounds right. But then …