The Servant was released in 1963 (in the United Kingdom), directed by Joseph Losey. Screenplay written by Harold Pinter, based on the novella by Robin Maugham (who was W. Somerset Maugham’s nephew). Stars Dirk Bogarde, James Fox, Sarah Miles, and Wendy Craig.

The film begins with a man walking down the street with a certain spring in his step. He’s swinging his closed umbrella just a little bit broader than his stride. It’s unclear what is his social status, especially when he enters a house that is in a state of disrepair. When he finds a young man asleep inside on the only chair within, it’s still not clear if he or the younger man is the owner of the house.

In fact, the sleeping man, Tony (James Fox), is the owner, and the walker, Barrett (Dirk Bogarde), turns out to be interviewing for the position of manservant. Tony just purchased the house with money inherited after the death of his father. He had slept away most of the day because of the previous day’s bender. Barrett presents his credentials and generally seem apathetic, perhaps disappointed at the state of his potential employer. He perks up when Tony asks if he enjoys this work, which he confirms, and is subsequently hired.

If the viewer is not careful, he might believe (as I admit I first did) this visual inversion of roles with Barrett being the servile, dependent one and Tony the dominant master. The truth is that Tony is mostly an unambitious drunk who depends on a manservant to make him a civil being as becomes increasingly clear.

Barrett assumes responsibility for the house’s renovation, down to almost the smallest details. Between Barrett and Tony things seem peachy. Tony needs drink early, and Barrett provides. Barrett brings meals to Tony as he sits outside and generally keeps everything running smoothly, even making suggestions about acquiring a cook.

Some friction begins, however, when Tony brings home his “fiancée” Susan (Wendy Craig). Susan finds it amusing that Tony’s hired a “manservant,” but it is not clear if it’s funny because it’s an outdated idea or otherwise. Susan finds increasingly reason for discomfort in Barrett, particularly one night when while they are reclining before the fire in a romantic moment and Barrett barges in. After Susan has left, Tony angrily chastises Barrett, but the moment is fleeting. It will become increasingly clear that Barrett aims to wedge himself between Tony and Susan.

The next day, when Susan tells Tony to get rid of him, Tony says two interesting things: (1) that Barrett is a human too, not merely an employee; and (2) that criticizing Barrett is in turn criticizing him because he has hired Barrett and his judgment is put into question. This defense impresses us because of Tony’s statement of his manservant’s humanity. While to our ears this must seem like a plain, uninteresting statement, such a description of that relationship is contrary to expectations (I know this because I’ve watched all of the Downton Abbey).

Around this same time, Barrett goes to a payphone where he makes a call to Vera (Sarah Miles), who he asks to come and visit him. It’s clear from the tone of their conversation that Vera is a sexual conquest. The scene is somewhat bizarre because a group of girls gather around the phone impatiently waiting for him to get off. Barrett does not respond to them with the gentility one might expect of his person and rank. Thereafter Barrett gives the news to Tony that his sister is coming to try out for the position of cook.

When Vera arrives, she is a very attractive young woman and appreciated in this respect by Tony, albeit with tact. She takes a room separate from Barrett. One weekend when Barrett has left town for a few days, she seduces Tony, and they become lovers. Tony repeatedly calls on her “services” whenever Barrett can be distracted.

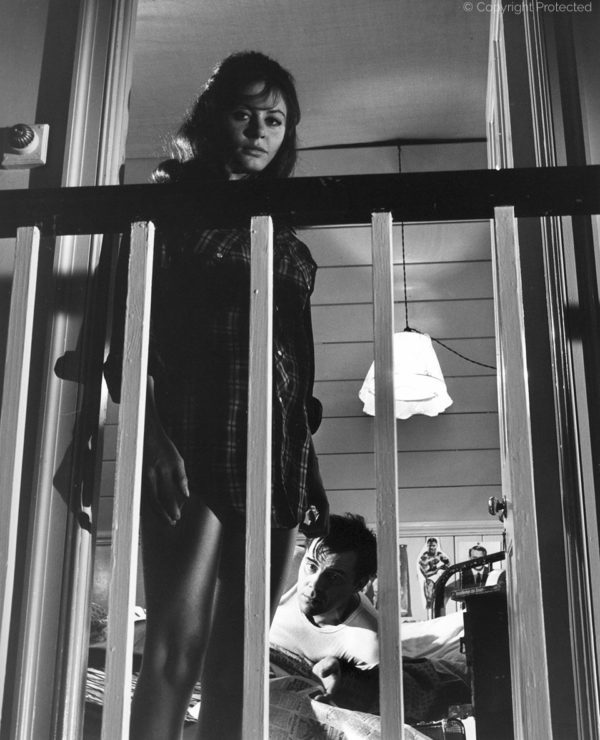

In one scene, Tony sneaks up the stairs and knocks on her door. She answers and promises to come down. After Tony’s gone down the stairs, she heads downstairs leaving the door open where Barrett sits in her bed. So, it is clear that Barrett knows what’s going on with Tony and Vera and submits to it with no sense of disapproval. Has Barrett planned all this so as to separate Tony and Susan or merely to enjoy cohabitation with Vera? If the latter …

Although Vera’s presence disturbs things between them, finally one weekend Susan and Tony are together for the weekend, outside of the city, and things between them seem to have been repaired. When they return early, they spy the light on in Tony’s bedroom. They enter the house quietly and hear Barrett and Vera enjoying Tony’s bedroom loudly. For the first couple moments after Tony and Susan have entered, as Tony realizes what is going on, his head rests against the wall or the bannister, exhausted.

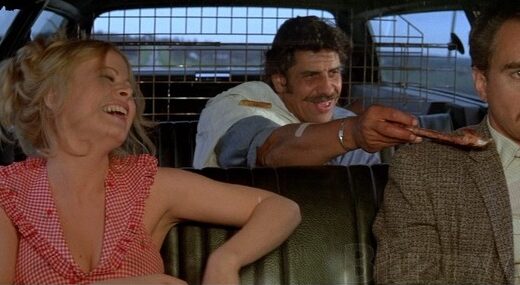

This confrontation should present Tony forcefully and angrily dismissing Barrett. Eventually he does, expressing horror, accusing Barrett of incest. But none of this disturbs Barrett’s peculiar equanimity. Barrett explains that Vera is not his sister but his fiancée. Only after Vera makes remarks in front of Tony and Susan implying that she had congress with Tony, does Tony demand that they leave. In fact, his denunciation and exile seem very much an act performed for the sake of Susan. Throughout the entire scene including as they collect their things, Barrett betrays not the slightest sense of embarrassment or guilt. In fact, as they are collecting their things Barrett seems to find the situation funny, comical, and of the least gravity.

What occurs next surprises no attentive viewer. The house falls into disrepair as Tony lives alone. He seems to be avoiding Susan’s calls. Then one day he happens into a bar and there inadvertently, or so it seems, meets Barrett. Barrett begs his forgiveness and explains that Vera had deceived him. He asks Tony for a second chance, which is granted. Clearly Tony is incapable of keeping up the house himself and must feel some guilt for having slept with Barrett’s fiancée. Perhaps this is why he employs Barrett once more.

And yet, attentive viewer or not, the narrative twist is unexpected.

But with Barrett returning, things are by no means the same. The relationship between Barrett and Tony has been inverted. Barrett bears few signs of responsibility for his former domestic duties. The house does not achieve the level of cleanliness it previously enjoyed.

What’s more, Barrett takes opportunities to criticize Tony for not keeping up a cleaner house, for not doing his part, for not having gainful employment. Barrett plies Tony with drink, and the two become more like roommates where Barrett seems to convincingly persuade Tony to make more of an effort to keep the house clean. Even Vera, Barrett’s “former” fiancée returns at one point, as Tony is wholly absorbed by his drinking. Barrett pushes the alcohol on him, as well as provides numerous other female consorts.

At a certain point, when Tony seems to demand his rights as the employer, Barrett explains the reversal: that Barrett is in fact the master, as he has performed all of the jobs around the house beginning with renovation and cleaning and taking care of Tony. Tony certainly cannot gainsay this point. He remains silent.

Finally, in the last few scenes Tony is never without drink, never not drunk. When Susan comes to visit, finally, she finds that not only has Vera moved back in, but that Barrett and Tony are hosting a group of women, perhaps “working girls,” each night. Susan recognizes Barrett’s triumph but still slaps him as she leaves the house.

The Servant is the second film I’d seen by Joseph Losey and Harold Pinter, the first being The Go-Between (1971). Again, I started watching these films because of a Criterion Channel collection of films whose screenplays were written by Harold Pinter. I’m not sure if I’ve read The Birthday Party, but I know that I’ve never seen its performance. In fact, I know little of drama, so this is part of my soul’s infinite (self-)tutelage.

In comparison with The Go-Between, it is surprising to think that The Servant had been produced by the same filmmaker (and screenwriter). While the narrative structure of The Servant is continuous, the motivations and statuses of the characters suffer great artistic violence. The Go-Between has a largely retrospective structure: an older man reflecting on a significant episode, visiting people related to this episode. But it was primarily a film directed by fairly conventional narrative expectations. What’s more, no characters disrupt their narrative expectations.

But in The Servant, the viewers’ expectations for a story confirming certain tacit social roles are completely overthrown. The relationship between a gentleman and his manservant is a longstanding trope of both literature and drama and film. Their respective roles reify the differences between wealth and want, nobility and servility, intelligence and ignorance. Tony is wealthy, but only because of money that he has inherited, not earned. It is not clear that Tony comes from an aristocratic background, or merely finally gained the means to pretend that he does.

I wouldn’t be much of a philosopher if I didn’t point out that this movie exemplifies the master-slave dialectic featured early in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. I’m not sure if that is significant. In fact, admitting that it is so somewhat bores me, for it makes me wonder if this screenplay was written mostly as a presentation of that well-known fragment of Hegel’s work.

Last thing: I was really impressed by Dirk Bogarde, of whose name I feel that I must have been previously aware (although I’m not sure that it’s just its resonance with Bogart). His character was fascinating. The viewer wanted to know more.