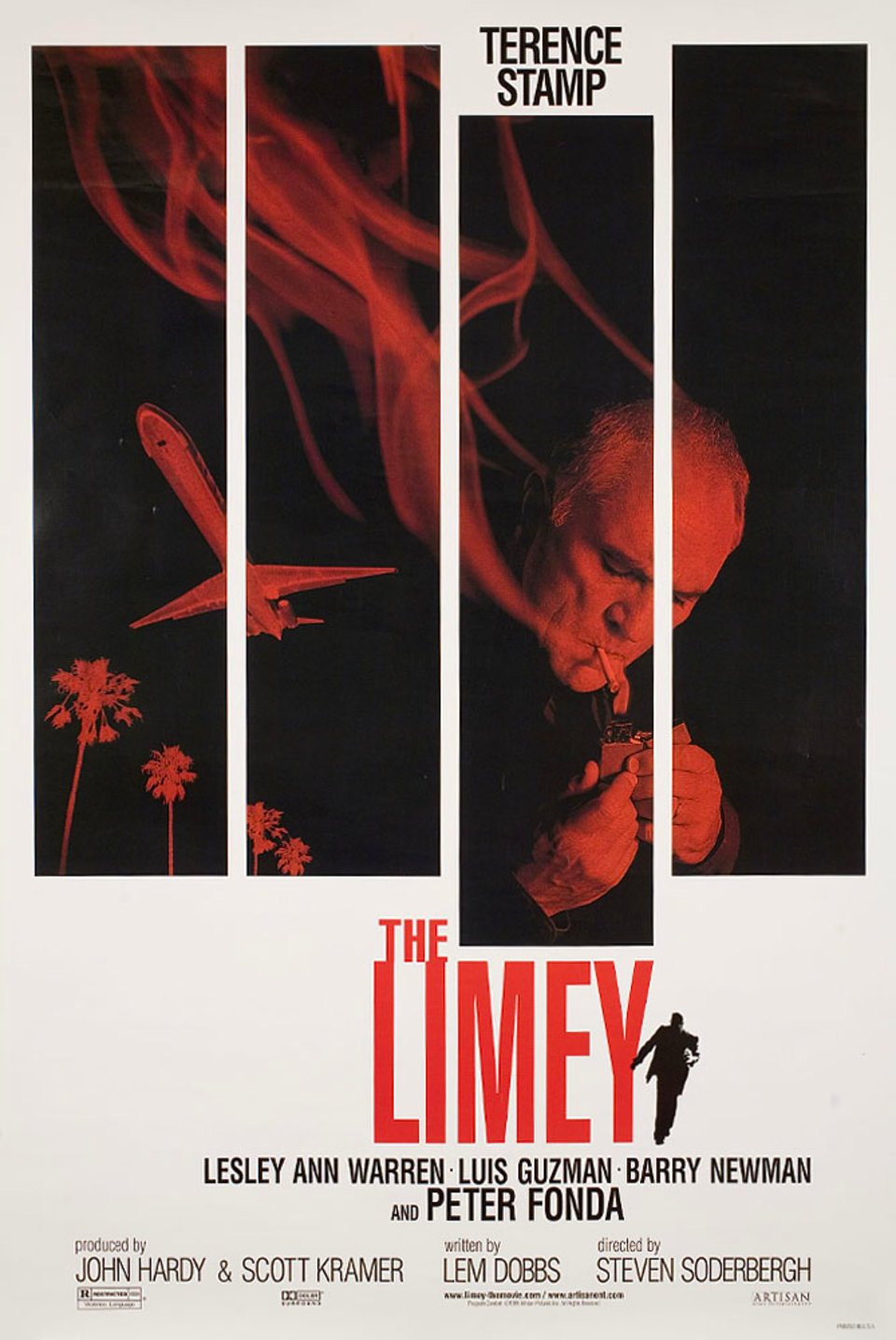

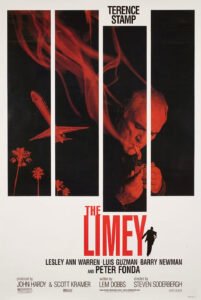

In 1999, Artisan Entertainment released American director Steven Soderbergh’s 6th film, The Limey. It is essentially a father-daughter story of a very strange sort, in at least two discrete dimensions. The film stars Terrence Stamp, Peter Fonda, and a cast of others characters familiar to Soderbergh films.

With a budget of $10 million, the $3.2 million it brought in through box office receipts made it a loss.

The Limey is About Aging Actors

Both Terence Stamp and Peter Fonda are B-actors who had developed careers long before this film, and those careers had sort of petered out.

Stamp had more success than Fonda did, working consistently until The Limey, albeit always playing marginal characters. One of his best films was the British film The Hit (1984), directed by Stephen Frears and co-starring John Hurt and Tim Roth.

By contrast, Fonda was in Easy Rider (1969) and then made a lot of bad films (and some bad bad films, like Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry [1974]) until Ulee’s Gold (1997), for which he won accolades and nearly a SAG award.

Who is Steven Soderbergh?

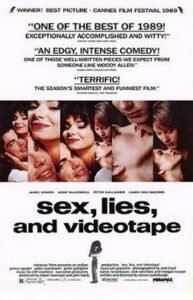

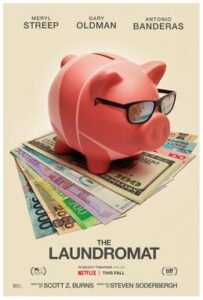

Steven Soderbergh is known for so many films today, if not especially for the Ocean’s Eleven (2001) franchise that is his early years have almost been forgotten. His first feature film was Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), which caused a stir once upon a time. The Limey (1999) he made a decade later, having completed six other films in that time (Kafka [1991], King of the Hill [1993], The Underneath [1995], Schizopolis and Gray’s Anatomy [1996], and Out of Sight [1998]).

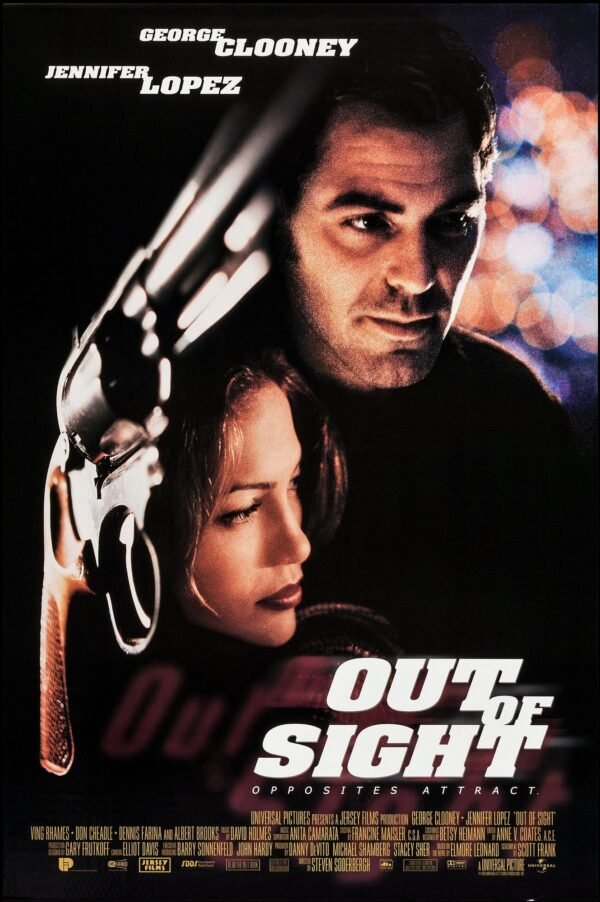

Of these, I think I’ve only seen Out of Sight — in fact, I think it was one of the first films that I’d seen by Soderbergh. The film marked the director’s name to my memory. I was really impressed by it although the story is not … great. Neither is it bad, but it was not to be one of the director’s best films.

Soderbergh made Out of Sight just before The Limey

Out of Sight stars George Clooney, Jennifer Lopez, Ving Rhames, and a young Don Cheadle. This is one of Clooney’s first roles where he is a complicated foolish character — in this case the romantic lead — where he excels. He’s frankly uninteresting in the roles like Danny Ocean in Ocean’s WGAF series. In Out of Sight he’s a non-violent felon, well meaning but foolish.

In The Limey everything is mise-en-scène

The Limey shares nothing with Out of Sight, a romantic thriller. None of the characters are developed through dialogue and scene, as in OoS. Instead, for The Limey everything is mise-en-scène.

Atmospheric effects imbuing each person with reality, where they lack the dialogue to make it so.

Examples of mise-en-scène

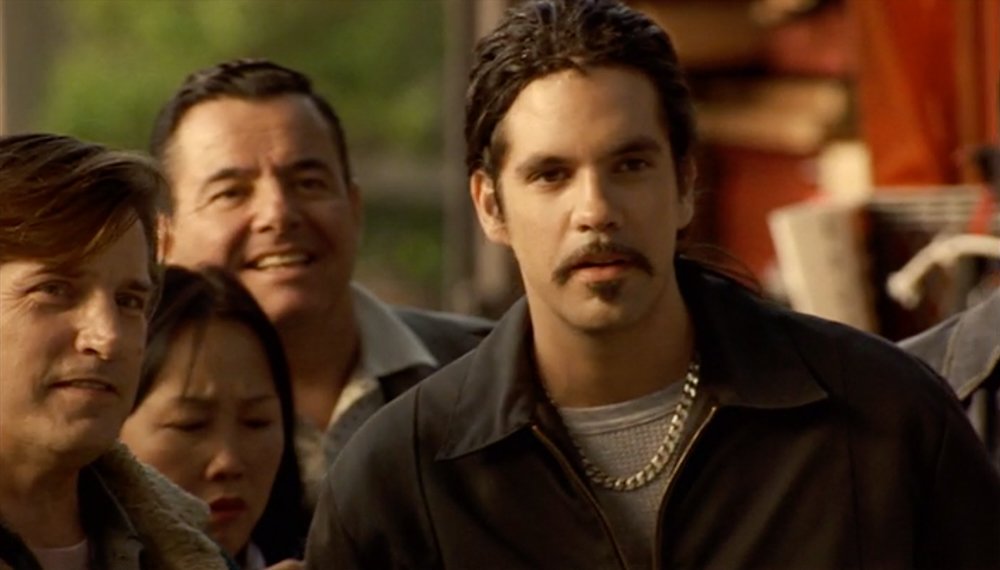

- Luis Guzmán’s character in his sister’s home, where he lives. An ex-con who still had the wherewithal to contact Jenny’s father despite not knowing him.

- Repeated shots of Wilson (Stamp) take place in the plane — never at his home in England where the decision was made to seek out his daughter’s killer. This fits with the sunny, lazy California aesthetic, whereas the UK couldn’t have done that. He’s not taciturn, but his dialogue fails to convey as much as the flashbacks.

In fact, Lew Dobb’s dialogue is the weakest part of the film. The dialogue presents Wilson as an ex-con, tough, blustery. Not a fool, but not capable of grace or subtlety. But he’s a grieving father, a father who’d never really been a father. His actions won’t change that. He just wants vengeance. Until he discovers that he inadvertently had a hand in bringing about her death.

This is interesting, for the epilogue of the film doesn’t find someone wearing a guilty conscience. Instead, he’s just a feckless traveler heading home.

Why is the dialogue so bad?

First of all, it’s not bad in the ways so common to Hollywood films. Instead, it’s energetic, entertaining. But it’s also glib. Too glib.

When characters wax poetic or cool, they have to be set up so that to do it, as the resolution of a moment. But there are no such moments in The Limey.

Instead, the dialogue becomes atmospheric — to the degree that expression makes sense — as it presents insignificant details that provide a background. Diegetically useless. There is no pistol introduced in scene 1.

Ex. 1: Nicky Katt’s character Stacy with sidekick Uncle John (Joe Dallesandro) talking about a job.

Uncle John: How much?

Stacy: Five grand.

Uncle John: Hey.

Stacy: Got half in my pocket.

Uncle John: We makin’ trouble for someone?

Stacy: Yep.

Uncle John: Which kind?

Stacy: [pause] … the forever kind.

Ex. 2: Wilson’s performance when meeting Bill Duke’s DEA chief.

Wilson: How you doin’ then? All right, are you? Now look, squire, you’re the guv’nor here, I can see that. I’m in your manor now. So there’s no need to get your knickers in a twist. Whatever this bollocks is that’s going down between you and that slag Valentine, it’s got nothing to do with me. I couldn’t care less. Alright, mate? Let me explain. When I was in prison – second time – uh, no, telling a lie, third stretch, yeah, third, third – there was this screw what really had it in for me, and that geezer was top of my list. Two years after I got sprung, I sees him in Holland Park. He’s sittin’ on a bench feedin’ bloody pigeons. There was no-one about, I could’ve gone up behind him and snapped his fuckin’ neck, *wallop!* But I left it. I could’ve knobbled him, but I didn’t. ‘Cause what I thought I wanted wasn’t what I wanted. What I thought I was thinkin’ about was something else. I didn’t give a toss. It didn’t matter, see? This berk on the bench wasn’t worth my time. It meant sod-all in the end, ’cause you gotta make a choice: when to do something, and when to let it go. When it matters, and when it don’t. Bide your time. That’s what prison teaches you, if nothing else. Bide your time, and everything becomes clear, and you can act accordingly.

Ex. 3: The DEA’s chief (Bill Duke) response after Wilson’s soliloquy.

There’s one thing I don’t understand. The thing I don’t understand is every motherfuckin’ word you’re saying.

Ex. 4: Valentine describing the 1960s

Did you ever dream about a place you never really recall being to before? A place that maybe only exists in your imagination? Some place far away, half remembered when you wake up. When you were there, though, you knew the language. You knew your way around. *That* was the sixties.

Ex. 5: Party banter

Excited Guy: [speaking to Valentine] That first Christopher Cross album? Wow, that record really changed my life.

This last one was pretty hilarious for me.