This site is about Ashley (U.) Vaught and the cultural products that he has consumed. So it’s about his consumption (and his corruption).

At its core, it’s about this very familiar saying, “You are what you eat.”

The saying calls attention to the types of food that we eat: if we eat junk food, then we are junk. Whereas I’m turning the phrase to the types of books and films and televisions shows we consume—and these days, it should be YouTube videos, Instagram Reels, Tiktoks, Facebook posts, tweets.

How do these books, films, etc. shape the person that I am? How have they affected me?

The human being (a biological concept) consumes foodstuffs in order to provide energy for its continued existence. Similarly, the self (a philosophical and psychological concept) eats, but it eats experiences and cultural products.

The word consumed is better suited to describing how we process cultural products. It sounds a bit strange to say that “one eats books, movies, and experiences.”

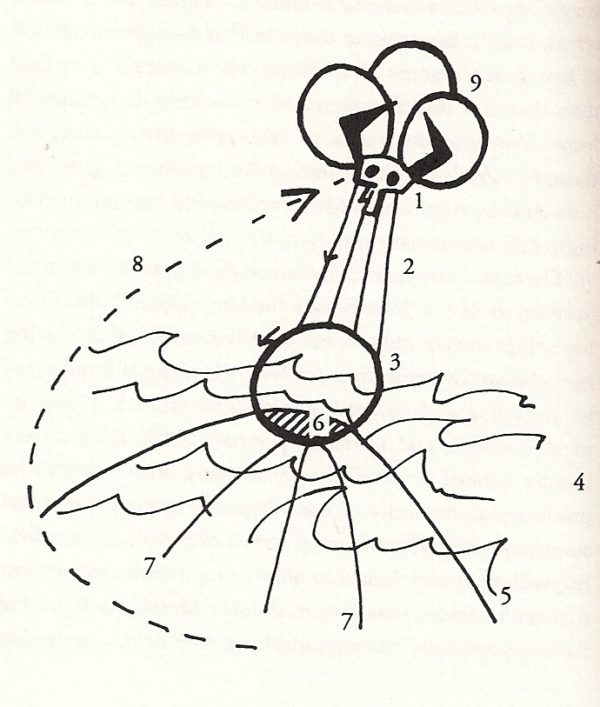

Cultural Consumption is not unlike Christian Communion

Consider the religious experience of the communion:

Having grown up as a preacher’s kid, I took communion many times. Communion is a ritual in which consumption is both corporeal and spiritual. The parishioner (me) eats the piece of bread and drinks the wine, and in so doing is incorporating (to incorporate is to take into the body) the body of Christ. During the ritual, the minister explains that the piece of bread represents Christ’s body and the wine (grape juice) represents Christ’s blood. So the parishioner is taking Christ’s body into his body.

But the effect of the communion is supposed to be spiritual. The parishioner wants to be filled with Christian spirit—he wants his spirit to be filled with the spirit of Christ.

I refer to communion as an analogy explaining what I’m trying to write about here, namely, how the books and films I have consumed have affected me in various ways.

The title of this page is a reference to Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (released the same year that Michel Tournier’s Friday, or the Other Island was published). I’ve always loved the glib, playful simplicity of that title.