Death Comes for the Archbishop, by Willa Cather, was published in 1927. These days the year 1927 means two years from the Great Depression and nine years from the rise of the NDSAP. Perhaps in the future it will mean nearly ten years after the “Spanish” influenza.

And you thought the past doesn’t change. Silly rabbit.

Among the lights that populate that period of literary history (Woolf, Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner, a green Katherine Anne Porter), Cather seems more like a vestige of the past because she is not overtly concerned with testing the formal conventions of a literary work.

This makes me wonder, is/was Hemingway concerned with testing the formal conventions?

But this judgment may be a bit premature. Death Comes for the Archbishop is not quite a novel, in that from the latter we expect an introduction of characters, a narrative arc developing the characters and conflict that drives the plot, and a resolution thereof.

But Death does not provide us with that. While it may be a narrative, it is not a novel. Rather, it’s a collection of stories that mainly have to do with the same characters throughout but include brief digressions that provide context for the two characters.

What happens in the “book”?

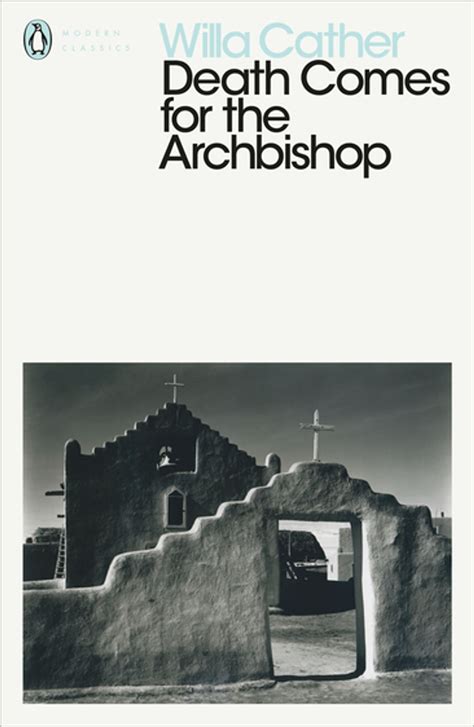

The two central characters, Father Vaillant and Bishop Latour, are French missionaries who’ve been directed by the Catholic church to travel to the New World and develop a diocese in late 19th-century southwestern United States—specifically what will become New Mexico and Arizona.

They travel there together, but most of their time in America is spent apart, diligently executing the many functions of their respective offices. In fact, they spend much time traveling on horseback (actually mules) from one parish to another. Religion, from the vantage point of the these characters, is a largely tiring administrative job.

This is not to say that the two characters fail to exhibit the signs of devotion or that they have doubts bedeviling (ahem) their faith. To the contrary, they are quite devout, but that is expressed through their mission not the expression of the doctrine or even personal testament.

The mission requires riding hundreds of miles for each task. Perhaps a reader might even find that aspect of the book repetitive, since it does occur so often. Yet the reflections of the characters—Bishop Latour in particular (to become in the last pages an archbishop before retiring from this position and then being taken by Death)—and the descriptions of the landscapes and the peoples are always eminently compelling.

In one passage the archbishop is describing a series of scents he encounters. The complexity of that description, the kinds of which I’ve come across in many books, always leaves me wondering why I don’t know the difference between all of those different scents. Would I even be able to recognize them? But the text then moves into how these scents are on the wane as the “civilization” of these natural landscapes occur, as though Cather had already anticipated my own poverty and provided an explanation therefor.

Why is it called Death Comes for the Archbishop?

The novel is not about Death coming from the archbishop, especially because, until the last chapter Latour is not an archbishop. The book’s title cannot help but conjure something like the Final Destination series of films with an archbishop rather than a feckless teen.

One of people in the bookclub to which I belong and for which I read this book claimed that the title of the book (and the last section, which was so called) was because in the conclusion of the book these characters were stripped of their mantles of sainthood. This is an interesting reading but I find that the portraits of most of the characters are very humanized and so I think no mantle-stripping actually occurs. As much fun as that sounds.